In modern society we take the night sky for granted. Astronomy is thought of as a fool’s errand (or worse, a nerd's errand) with no commercial benefit. But since the dawn of human curiosity, the three thousand stars visible to the naked eye have inspired great literature, art and science. The phases of Venus and the moons of Jupiter helped show that we live in a universe not centred on the Earth. The pirouetting motion of the moon around the Earth and the Earth around the Sun led inexorably to the idea of gravity. The observation of light from distant galaxies tore down the eternal notion of the universe and gave it a start date. All this from sitting on the ground, observing the sky above.

|

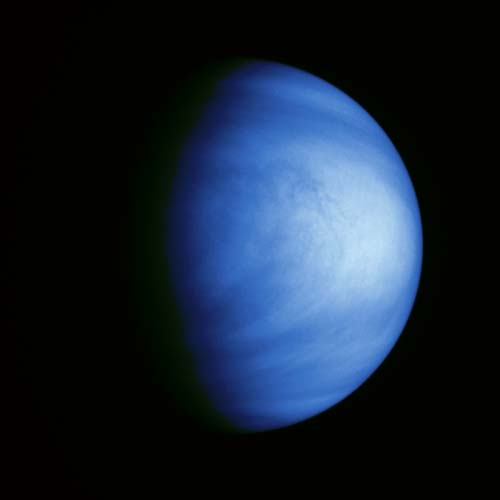

| The thick clouds of Venus (nasa data centre) |

But imagine, if it is possible, a world enshrouded by impenetrable clouds; with nights remarkable only for their lack of daylight. These planets do exist. Far above Venus’s highest peaks exists a thick sulphuric acid cloud layer that scatters all light away. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is also covered by haze, this time created by hydrocarbon molecules such as ethane. Even the Earth has its own layer – if human eyes were adjusted to a wavelength around 1mm we would see a star-consuming haze above caused by atmospheric water.

So, how would humanity have developed if the night sky was devoid of the features we take for granted now? It seems certain that humanity’s perception of our place in the universe would change - lives will be played out in two dimensions, as if sandwiched between two sheets of paper. In this parallel reality, the world would probably be thought of as flat until the time of global exploration.

Even if the study of mathematics, thermodynamics, electricity and magnetism continued, without observations of the other planets, the system of an Earth-centred universe may well have persisted. The idea of gravity would also be a relative late-comer, developed only after the force theories of electricity and magnetism. Not only would the theories of physics be different, but so would any notion of how our world formed. Only through observing our own solar system (and others) have we theorised how our planet and the seven other planets around our sun were formed. Without the night sky to prove this, ancient creation myths will have endured.

However, suppose this hypothetical civilisation reached a technological age. Having lived under cloudy starless skies for an eternity, picture the moment when the first ever rocket to carry humans above the thick hazy atmosphere arrived. Until pictures could be taken and developed, the stories of those first few astronauts would almost certainly be met with disbelief. After this eureka moment, the perceptual shift would be incomprehensible. Where before there was nothing but grey haze above, there was suddenly a universe teeming with stars. Planets circle in eccentric orbits around a great shining ball of fire at the centre of the solar system. Galaxies spin millions of light-years away containing a hundred billion suns. And this is what we get to see. Every night. The most amazing thing is that no one seems to realise how lucky we are.